Object Properties

We took a few dozen object properties from Wikipedia.org and created a word cloud.

Directly Measured Object Properties

You will see dozens to thousands of unique objects if you look around. Every object has boundaries, physical states, and unique, measurable properties that differentiate it from other objects. Even seemingly identical objects, such as textbooks, are different because they have unique locations. You already have the tools and the skills to easily measure many properties, such as length, width, height, mass, temperature, etc. And with a bit of help and the right tools, you could measure other properties such as melting point, boiling point, luminance, etc.

All of the descriptors mentioned so far refer to specific object properties that you can easily measure. But there are also object properties that you must calculate.

Calculated Object Properties

Several Thousand Object Properties Extracted from Wolfram Mathematica (click to zoom in). Word Cloud by Royal Circuits

Velocity

Velocity is a calculated property usually determined by recording the position at two instants in time and calculating the quotient of the displacement and the time interval.

Other methods exist to measure the velocity of an object utilizing the Doppler effect, a flowmeter, differential manometer, etc., but no method exists to measure velocity at a given instant in time directly; we must calculate or infer it over some time interval.

Momentum

Momentum is a calculated quantity that combines the measured property mass with the calculated property velocity.

Knowing the momentum of a single object isn’t very useful, but knowing the momentum of several objects or the change in momentum of a single object is useful.

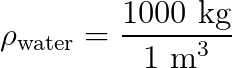

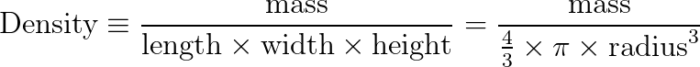

Density

Density is a calculated object property, defined as the ratio of mass to volume.

We know, from experiment, that a cube of water, 1 meter on each side, has a mass of 1000 kg.

That gives water a density of 1000 kg/m3. It doesn’t matter how much or how little water you have, the equivalency will always hold true. Smaller volumes of water will have a proportionally smaller mass.

The shape of the tank also doesn’t matter. If your water is in a cubic tank, you can find the volume as the product of the lengths of the sides. If, instead, you decide to hold it in a giant balloon or beach-ball, the volume becomes the product of four-thirds pi times the radius cubed.

The takeaway is that you can change the shape of the container, and the density will remain constant. The equations you use to calculate density might change, but the result of the calculations and the property of density for a given substance will remain constant.

Many calculated object properties are tangible. You can look at an object and instinctively know if the velocity is high or low. You can hold an object in your hand and feel if the mass is high or low, and then intuit if the density is higher or lower than you might expect.

Okay, So What is Energy?

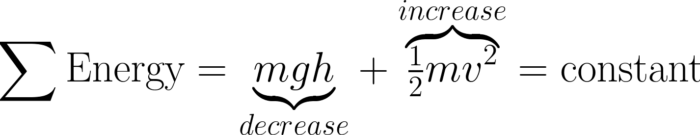

Energy is a calculated object property. It doesn’t exist outside of various mathematical equations. But the equations link a physical property from one equation with a different property from another equation. For example, you might see the height of an object decrease in one equation while velocity simultaneously increases in another equation.

What differentiates Energy from other calculated object properties is that you can calculate it a several dozen ways using equations that incorporate multiple object properties. The equations you choose depend on the properties and circumstances of the situation. It takes quite a bit of practice and repetition to recognize which properties to choose based on the circumstances.

The units of Energy are “Joules” after James Prescott Joule, a scientist who helped to develop the idea of Energy.

Let Me Repeat My Question. What is Energy?

Energy does not exist outside of our imaginations. Scientists and engineers made it up to better understand engines and thermodynamics, then applied the concept to other branches of physics. There is no physical incarnation of something called Energy.

What does exist are various tangible object properties (mass, velocity, acceleration, volume, temperature, etc.) and equations that allow you to calculate a value for the calculated property energy from various easily measurable and certainly real object properties. That makes equations for Energy the common thread that links otherwise seemingly unrelated things.

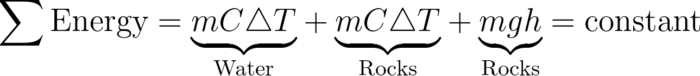

Here is a quick example. It turns out that if you drop a collection of rocks into a pond from a significant height, the temperature of both the water and the rocks will increase. But by how much?

Some equations define the change in Energy based on the change in the height of an object, and other equations define the increase in temperature based on a change in Energy. Put the two together, and you can find a solution very quickly.

But without the concept of energy, there’s not really a way to tackle the problem other than experimentation.

Back to the Problem of Steam Engines

Let’s go back to our example of the steam engine and how scientists and engineers had the unenviable task of finding a common mathematical link between fuels, engines, ships, trains, and travel distances. They needed equations to determine how to maximize performance and minimize development costs.

From experiments, scientists determined that one kilogram of coal has 24 million units (Joules) of energy associated with it. When the coal burns, 24 million Joules of Energy comes out as heat energy, and that heat can boil water and make steam.

Scientists also know, from experiment, that it takes 4184 Joules of energy to raise the temperature of water by one celsius degree.

So if you know the mass of water you’re working with and know the amount of heat energy that your fuel produces, you can determine the rise in water temperature.

That’s quite the temperature increase for a cubic meter of water. Try to imagine that much water on your stove at home, and imagine how long it might take you to bring it to a complete boil. You’ll be in the kitchen for a very long time!

What is Energy As It Applies to Electronics?

Remember, Energy doesn’t exist. It is a calculated object property. And it is calculated from lots of different properties. So a better question might be, “what equations and object properties are useful in studying electronics?”

We’ll introduce several of them as they become relevant in the rest of this Back-To-Basics series.